A global health certification system tied to a QR code

Not something dreamed up by David Icke or Alex Jones, but actually part of what the World Health Organisation is trying to impose in its amendments to the International Health Regulations.

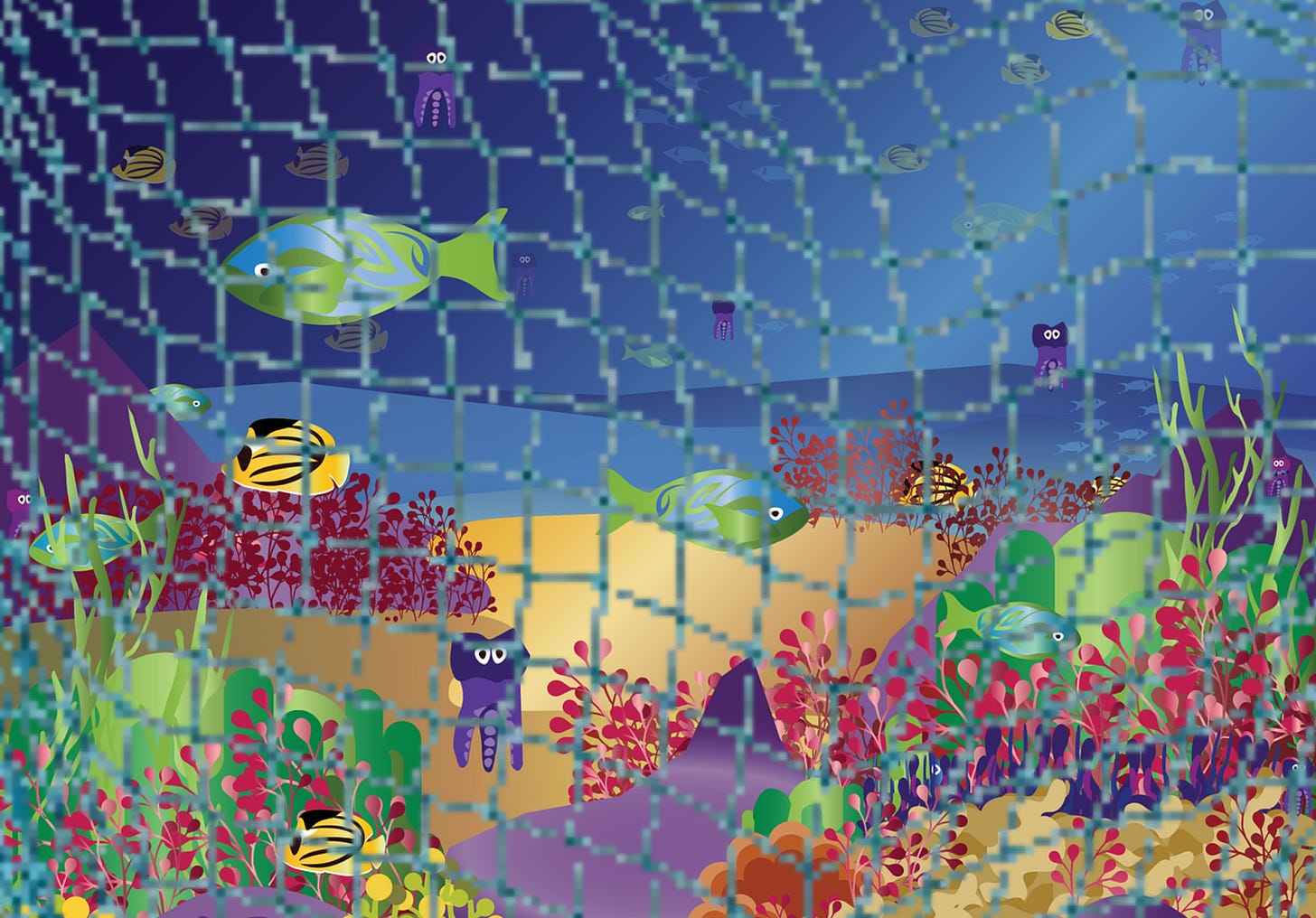

I often feel as if we’re all caught up in a global dragnet, with most people swimming around busily, blissfully unaware that the net surrounds them and is gradually tightening. As it tightens, more people start to notice it – many quickly turn away, trying to convince themselves that they haven’t seen what they just saw. In any case, by this time it’s too late… or is it?

Last night I watched the Westminster Hall debate on the e-petition relating to the International Health Regulations currently being motored through the world’s democracies by the World Health Organisation. I agreed with almost everything that most of the speakers said, and thoroughly enjoyed watching them, but at the end of the debate I was left with a sense of desolation, a feeling that such a debate can have little impact on policy, that we’re up against a monstrous machine that is set on destroying anyone who gets in its way.

The points that stood out for me included the following.

Mark Francois summarised the some of the most drastic amendments.

“…first, amendments to make WHO emergency guidance legally binding—it is currently only advisory—on member states; and secondly, amendments that would empower the WHO director general to single-handedly declare a public health emergency of international concern…

“Thirdly, there are amendments to implement an international global health certification system enabling nations to enforce travel restrictions using tools such as vaccine certificates, passenger locator forms and travel health declarations—all tied, potentially, to a personal QR code.

“Fourthly, there are amendments that would increase censorship of dissenting voices by mandating systematic global collaboration to counter dissent to official governmental or WHO guidance.

“Taken together, the proposed amendments empower the WHO to issue requirements for the UK to mandate highly restrictive measures, such as lockdowns, masks, quarantines, travel restrictions and medication of individuals, including vaccination, once a PHEIC (“Public Health Emergency of International Concern) has been declared by the WHO.”

Sir Christopher Chope made reference to the WHO’s corporate backers.

“The WHO is also beholden to some of its big donors; if one analyses how the WHO is funded, one sees that organisations such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation are significant supporters. He who pays the piper calls the tune.”

In fact, a very significant proportion of the WHO’s funding comes from pharmaceutical companies, and GAVI, the global vaccine alliance, is one of its biggest funders.

Nine speakers participated in the debate, out of a total of 650 MPs. They were almost all Conservative, apart from Andrew Bridgen (Reclaim) and Preet Kaur Gill (Labour). No SNP or Liberal Democrat MPs were present, or any other parties. There was no Scottish, Welsh or Irish representation.

We went from a position of trust in the state to profound scepticism.

The points that Danny Kruger made resonated very strongly with me. He made reference to the low numbers of speakers and suggested a reason, saying:

“It is worrying that so few Members are present. This is a fringe issue in Parliament, as demonstrated by the empty Benches, but significant numbers of the public have a real interest in this topic, so what is going on?”

He then hinted at a kind of cognitive dissonance at play, a reluctance among many MPs to face up to certain facts.

“…we want, as individuals and citizens, to trust in the Government when it comes to healthcare. We really do. That is why we have such a commitment to the NHS in our country. We want the state to be trusted, authoritative and capable when it comes to our health. We instinctively recoil at suggestions that there is a problem when it comes to the management of healthcare, and yet, as we have heard today from colleagues who put the details very well… there is clearly a difficulty, a challenge, a problem with the proposed regulations and treaty.”

I think he echoed the feelings of many of us when he said:

“We should be concerned about the value of the World Health Organisation, given its record, and we should, I am afraid, have the same scepticism about our Government’s role. The trust that we all desperately want to have in healthcare has been badly tested by the experience of recent years.

“We (referencing comments made by Mark Francois) went from a position of trust in the state to profound scepticism.”

He added that more global co-operation was not the answer.

“The problem during the whole covid episode was not the lack of international co-operation; there was a very high, remarkable, degree of that. Almost every country did exactly the same thing, following China’s example. What we did not have enough of was independent decision making at nation state level.”

Preet Kaur Gill, Shadow Minister for Primary Care and Public Health, was present to represent the Opposition. Her initial comments, about “hundreds of thousands of deaths”, learning lessons and taking steps to strengthen our resilience for the future, immediately put me (and clearly people in the visitors gallery) on edge. It came across as dismissive of the genuine concerns about global overreach and potential tyranny that had been so eloquently expressed by the previous speakers, and condescending, as if people who hold such concerns did not even realise or cared about the suffering and deaths that had occurred.

She continued:

“The lesson of the pandemic was that no one is safe until everyone is safe, so it is clear that global co-operation on pandemics and biological threats needs to be strengthened. Labour absolutely supports the principle of legally binding international health regulations that define the obligations of countries in handling pandemic-level threats. That is critical to our national health security.”

An AI bot could have made that statement. It completely ignored the very important concerns that had just been detailed by the handful of MPs who were putting their own careers at risk to actually represent the views of many of their constituents.

Andrew Stephenson, the Minister for Health and Secondary Care, went into more detail about the implementation of the IHR and whether it could jeopardise national sovereignty. In response to a question from Mark Francois on whether the WHO could potentially impose a lockdown on the UK without our approval, he replied:

“I can give a categorical reassurance to my right hon. Friend that that is a red line for the UK Government. We would never allow the World Health Organisation to impose a lockdown in the UK. That is a clear red line for us. I cannot think of any Minister who would agree to such a request.”

This might sound reassuring, but how much can we trust the word of a politician? And what happens if a different party comes to power?

The good thing about these debates are that they put the issue on official record. Apart from that, is there any point to them? Maybe the government benefits most from e-petitions, as they are a gauge of popular concerns. Writing in the LSE British Politics and Policy blog, Cristina Leston-Bandeira, Professor of Politics at the University of Leeds, says:

“For protest petitions, a debate is part of their safety valve role”.

Maybe an indication of the value that governments really place on the concerns and opinions of the people they rule over?